Gianbattista Tiepolo

Giambattista

Tiepolo, Italy's greatest eighteenth-century painter, was born in

Venice in 1696, and died in Madrid in 1770. Though his godfather was a

Venetian nobleman, Giambattista was the sixth son of a tradesman, the

part-owner of a commercial boat. The father died a year later, and the

boy was subsequently apprenticed to Gregorio Lazzarini, though seems to

have learned more from his older contemporaries, Sebastiano Ricci and

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta. Giambattista's first major commission,

finished at the age of 19, was the Sacrifice of Isaac. In 1717 he left

the Lazzarini studio, and joined the Fraglia guild of painters. Two

years later he married Maria Cecilia Guardi, sister of the painters

Francesco and Giovanni Antonio Guardi, with whom he had nine children,

four daughters and three sons surviving into adulthood. Two sons,

Domenico and Lorenzo, became his assistants and noted painters in their

turn.

Giambattista

Tiepolo, Italy's greatest eighteenth-century painter, was born in

Venice in 1696, and died in Madrid in 1770. Though his godfather was a

Venetian nobleman, Giambattista was the sixth son of a tradesman, the

part-owner of a commercial boat. The father died a year later, and the

boy was subsequently apprenticed to Gregorio Lazzarini, though seems to

have learned more from his older contemporaries, Sebastiano Ricci and

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta. Giambattista's first major commission,

finished at the age of 19, was the Sacrifice of Isaac. In 1717 he left

the Lazzarini studio, and joined the Fraglia guild of painters. Two

years later he married Maria Cecilia Guardi, sister of the painters

Francesco and Giovanni Antonio Guardi, with whom he had nine children,

four daughters and three sons surviving into adulthood. Two sons,

Domenico and Lorenzo, became his assistants and noted painters in their

turn.

From 1726 to 1728, the young Tiepolo undertook the fresco decoration of the chapel and palace of the Friulan town of Udine, where his pale tonalities and airy handling announced a revolutionary talent of the first order: the theatrical grandeur of the Baroque was retained but transposed to lighter, more decorative chords. Enormous canvases to decorate a large reception room of Ca' Dolfin in Venice followed (1726–29), and then a rapid succession of paintings for churches, villas and palaces: Verolanuova (1735-40), Scuola dei Carmini (1740-47), Scalzi 1743-44), Palazzi Archinto and Casati-Dugnani (1731), Colleoni Chapel (1732-33), Gesuati (S.Maria del Rosario), Palazzo Clerici (1740), Villa Cordellini (1743-44) and the Palazzo Labia (1745-50).

By 1750 Tiepolo was famous throughout Europe. He painted the world's largest ceiling fresco for Prince Bishop Karl Philipp von Greiffenklau at Würzburg in 1750, returning three years later to Venice, where he was elected President of the Academy of Padua. More commissions followed: frescoes for patrician villas and church altarpieces. In 1761 he was commissioned by Charles III to decorate the throne room of the royal palace of Madrid, and there, on March 27, 1770, he died. With the decay of absolute monarchies, the Rococo style was gradually replaced by Neoclassicism, and then by the citizen concerns of revolutionary France, but Tiepolo's sons maintained the mixture of rich colour and fluid design, though in a more intimate, socially-observant manner.

Rococo

Rococo derives from French word 'rocaille', the shell-covered rock work used to decorate artificial grottoes, and refers to the eighteenth-century taste for elegance, lightness of touch and exuberant use of curving, natural forms of ornamentation. The French painters of significance are Antoine Watteau, François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, each greatly gifted in different ways. From France the style spread in the 1730s to the German-speaking Catholic lands, where it combined French elegance with south German fantasy in religious and secular architecture of great brilliance. In Italy the style was largely restricted to Venice, where it gave expression to that city's love of carnival and refined ostentation.

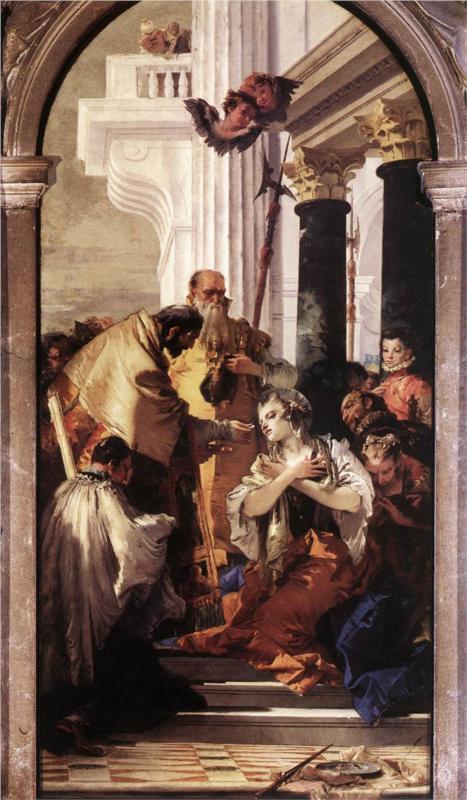

Its greatest exponent was Giambattista Tiepolo, who produced a continuous stream of frescoes, altarpieces, portraits, drawings and pen and ink works that combine astonishing technical facility with intelligence and imaginative expression. The frescoes are flamboyant masterpieces of airy nothing, as unreal as anything emanating from Hollywood, but with extreme refinement and aristocratic hauteur. The male portraits are of real people but those of women tend to adopt a formula (albeit convincing) of suave voluptuousness. The altarpieces vary. Some are dutiful or even vapid, but the best are as poignant as anything Spain produced, with greater flair, taste and and imagination. The martyrdom of St. Lucy has an idealized woman, but still expresses intense religious fervor, in the saint and the attendant figures: all play their parts faultlessly.

Rinaldo

Enchanted by Armida: Detail

Rinaldo

Enchanted by Armida: Detail