Peter Paul Rubens

Peter Paul Rubens was born in 1577 to the lawyer and diplomat Jan Rubens of Siegen, Westphalia, and died in Antwerp in 1640. His first employment was in court life, as a messenger to Marguerite de Ligne, Countess of Lalaing, but he returned to Antwerp and studied under three local masters and in 1598 was accepted as a master in the Antwerp painters' guild. The 1600-08 period found him in Rome, where, between studying the Italian masters and the sculptures of antiquity, he painted three altarpieces for the Church of Sta Croce in Gerusalemme. Rubens came back to Rome in 1605, painted the altarpiece for Santa Maria in Vallicella, replaced it with three pictures painted on slate, and returned home to Antwerp in October 1608 on hearing his mother was ill.

His mother had indeed died, but Rubens was deterred from going back to Italy by being appointed court painter to the Archduke Albert, the acting ruler of the Spanish Netherlands. In October 1609 Rubens married Isabella Brant, and over the next twelve years became the leading master of the city, establishing a fully automated workshop employing the likes of van Dyck and turning out an enormous quantity of secular and religious work.

In 1622 Rubens went to Paris and began a series of twenty-one large canvases for the Luxembourg Palace, tapestries for Louis XIII and, later, an even larger tapestry cycle for the Convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid. He also held important diplomatic posts, and helped bring about peace between Spain and England. Isabella Brant died in 1626, and in December 1630 Rubens married Helena Fourment, a girl of sixteen. He gradually succeeded in withdrawing from diplomatic life and purchased a country estate some miles south of Antwerp, dividing his time between this retreat and his town studio. In 1635 he was tasked with preparing the street decorations commemorating the visit of the new governor of the Netherlands, in which teams of artists and craftsmen realized his designs and exceeded all expectations. His last project was a vast cycle of mythological paintings for Philip IV's hunting lodge near Madrid, the Torre de la Parada, but arthritis made him give up painting towards the end of his life. He died in Antwerp on May 30, 1640 seemingly content with a vast output matched by a Europe-wide reputation.

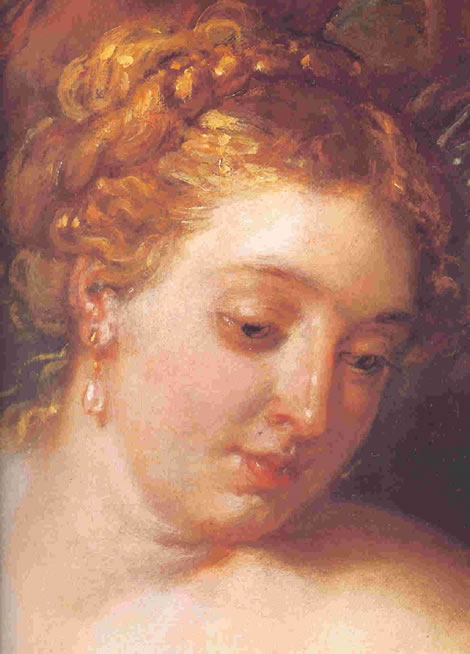

Peter Paul Rubens was able to breathe new life into the attenuated forms of Mannerist painting and, by fusing Flemish realism with Italian Classicism, create a powerful and exuberant style that came to characterize the Baroque art of northern Europe. His figures, realistic, fleshy and indeed corpulent, are set in dynamic compositions that echo the grand organizations of the Renaissance masters. He toured Italy, sketchbook in hand, to learn from Titian and Raphael in particular, and his gifts — he was a noted classicist, diplomat, scholar, antiquarian, humanist and master of several languages — allowed him to mix biblical stories, Catholic theology and Greek and Roman history and mythology in styles congenial to his princely and religious patrons. Modern conceptions of genius notwithstanding, Rubens was an energetic, prosperous and balanced man who stayed a devout Roman Catholic, a loyal subject of the Spanish Hapsburgs, and the devoted father of eight children by two wives.